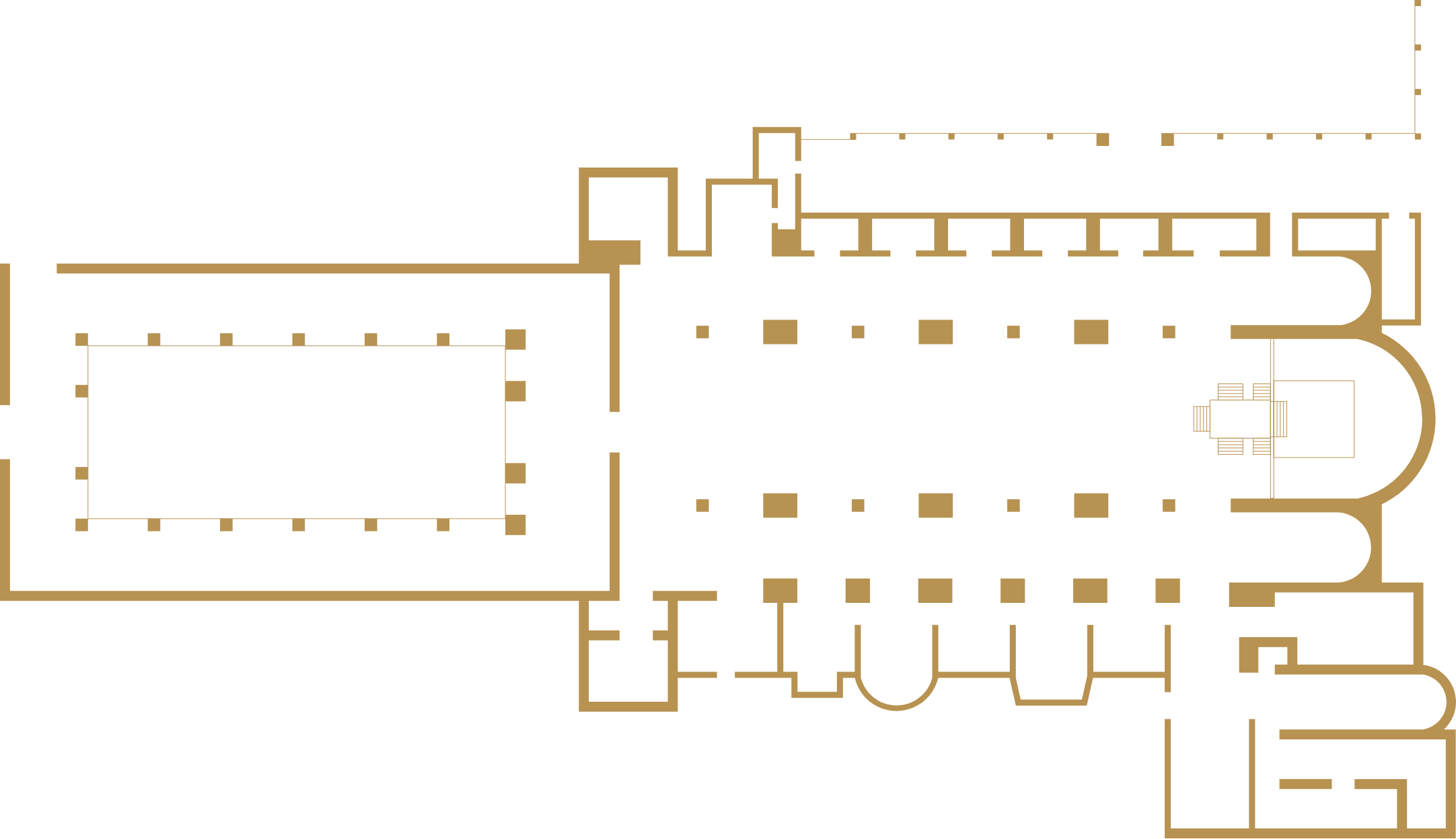

The Basilica’s Romanesque atrium stands on the site of the one built in the ninth century by Archbishop Anspertus (†881), as we read on his tomb epigraph: ‘he built the atrium in front of the nearby doors’ (‘Atria vicinas struxit et ante fores’). The atrium proper has three sides, connected to the large narthex that was built right up against the Basilica’s façade. This porticoed space was a gathering place for the faithful preparing to be baptised (catechumens) and public penitents. During the Middle Ages, the atrium hosted pilgrims, a market and public assemblies and it also served as a cemetery, as attested by the numerous tombstones mounted on the walls. In the early Middle Ages, the presence of two quarrelling religious communities, the canons and the monks, resulted in the construction of two separate bell towers: one for the monks, to the right of the facade and dating to the ninth/tenth century, and one for the canons, to the left of the facade and built in 1128 (later raised in 1889 by Gaetano Landriani).

The basilica

The venerated burial site of St Ambrose, the Basilica has witnessed more than sixteen centuries of the life of Milan and its people.

THE ATRIUM OF ANSPERTUS AND THE BELL TOWERS

MAIN PORTAL

The main portal, crowned by reused fragments of ninth or tenth century marbles and emblazoned with a lamb, mystical symbol of Christ, on the architrave, preserves its original decorative programme, which is focused on episodes from the life of King David and attributed to Ambrose himself. The two elm-wood panels are, although quite worn, of particular note and depict David with his Flock; Samuel Meeting Jesse and his Sons; David Called Home and the Anointing of David. Other original elements are preserved in the frieze with Angels Holding Up the Chrismon (a monogram of Christ). The two bronze door knockers in the shape of lions’ heads are from the early Middle Ages. When the portal was restored in 1750, the original panels were removed and the sequence of the episodes from the life of David was changed, as we read in the commemorative inscription.

SARCOPHAGUS OF STILICHO AND MEDIEVAL AMBO

One of the few surviving vestiges of the basilica built by Ambrose, the ‘Sarcophagus of Stilicho’ (fourth century) is still in its original location. Held to be the tomb of the magister militum Stilicho (†408) and his wife Serena, it is of the ‘city gate’ sarcophagus type, so named for the depiction of turreted gates in the background. The side facing the nave is decorated with the Traditio Legis, or Christ seated among the Apostles, delivering the Law to Peter. On the opposite side, we see a young beardless Christ teaching. The ends are decorated with Biblical scenes, including one of the earliest western representations of the Nativity. In the twelfth century, the sarcophagus was incorporated into the Romanesque pulpit, which is decorated with symbolic animals and human figures supporting architectural structures (telamones). Partially destroyed by the collapse of the bay in 1194, the ambo was rebuilt under the direction of Guglielmo de Pomo in the early thirteenth century.

THE GOLDEN ALTAR

One of the greatest masterpieces of Carolingian art, the Basilica’s high altar is a reliquary-tomb that was commissioned by the archbishop of Milan, Angilberto II (824–859), for the bodies of Ambrose, Protasius and Gervasius, ‘a treasure more precious than any metal’, as we read in the niello dedicatory inscription on the back. The altar is composed of a wooden box covered with embossed panels embellished with cloisonné enamel, gems, pearls and coral, depicting episodes from the Life of Christ on the gold front and, in parallel, those from the Life of Ambrose on the gilt silver back, which faces the apse. The sides are decorated with the saints of the Milanese Church, the Adoration of the Cross and the link to Martin of Tours, patron saint of the Carolingian empire. The complex decorative programme celebrates the glory of Ambrose and the dignity of the Milanese Church, embodied by a splendid ‘Ark of the Covenant’. It was made by skilled artisans led by the mysterious magister phaber Volvinus, who is shown receiving a royal crown from Ambrose, like Archbishop Angilbert, in the central medallions decorating the doors providing access to the saints’ tomb

CIBORIUM

The ciborium, which towers above the altar supported by four late antique porphyry columns, probably dates to the Carolingian period. At the end of the tenth century, it was decorated with elegant polychrome stucco work, possibly for a royal coronation. The west side, which faces the faithful, depicts the Traditio legis, with Christ delivering the keys to Heaven to St Peter and the law, in the form of a scroll, to St Paul. The east side, which faces the clergy, depicts Ambrose’s election as bishop, flanked by the martyrs Protasius and Gervasius, who present the archbishop-patron with a model of the ciborium, and a deacon. The scenes decorating the north and south sides are difficult to interpret but are probably linked to the Ottonian dynasty. On the north side, two women pay homage to Mary, representing the universal Church, or St Marcellina. On the south side, two male figures wearing crowns prostrate themselves before a bishop (possibly Ambrose).

APSE MOSAIC

The apse mosaic, the result of modifications and repairs carried out between the late antique period and the twentieth century, depicts Christ Pantocrator making the blessing gesture and the martyrs Protasius and Gervasius being crowned by the archangels Michael and Gabriel. In the eleventh century, medallions with portraits of St Marcellina and St Satyrus (Ambrose’s sister and brother) and St Candida were added. There are two unusual scenes on the sides: Ambrose, who appears to have fallen asleep during Mass in Milan (on the right), is simultaneously officiating at the funeral of St Martin in Tours (on the left). The central group of Christ and the martyrs is late Byzantine in style, with early thirteenth-century repairs, while the iconography of the episodes on the sides underlines the link between Ambrose and Martin, patron saint of the French empire, which was developed in the ninth century by Angilbert II, archbishop of Milan, to integrate the Milanese Church into the Carolingian political and religious programme. The current appearance of the mosaic is the result of the almost total reconstruction of the apse after it was heavily damaged by bombardments in 1943.

BRAMANTE’S CANONICA

In 1492, Cardinal Ascanio Sforza, brother of the duke of Milan, Ludovico il Moro, commissioned Donato Bramante (1444–1514) to rebuild the clergy house and update the basilica’s chapels. In 1497, the architect also began work on the total reconstruction of the adjacent monastery, which had passed to the Cistercian order. The initial project for the clergy house entailed a square porticoed courtyard with a large triumphal arch in the middle of each side. Only one of them was built, in front of the monumental portal, and decorated with marble busts of Ludovico il Moro and Beatrice d’Este. Heavily damaged by bombing in 1943, Bramante’s portico was restored by the architect Ferdinando Reggiori, who painstakingly recovered the surviving original fragments.

TOMBS OF AMBROSE, PROTASIUS AND GERVASIUS

In 386, Ambrose found the bodies of the martyrs Protasius and Gervasius near the old church of Santi Nabore e Felice, and had them placed beneath the altar of the Ambrosian basilica, in the marble-clad tomb that he had had prepared for himself. After his death (4 April 397), Ambrose was buried there as well, in a tomb to the left of the martyrs. In 1864, the parish priest Francesco Maria Rossi unearthed a porphyry sarcophagus, which was resting on two empty tombs placed side by side and clad in precious marble: these were the tombs of Protasius and Gervasius (larger in size) and Ambrose. The porphyry sarcophagus, where the relics had been placed in the ninth century, was opened on 8 August 1871 and found to contain the remains of the three saints, placed side by side, immersed in water and well preserved. In 1897, a new urn was made for the saints’ relics. Designed by Ippolito Marchetti, the glass and embossed silver urn was paid for with contributions from Milan’s leading families and still preserves the saints’ bodies today.

SAN VITTORE IN CIEL D’ORO

Among the ancient edifices (cellae memoriae) commemorating the martyrs buried in the necropolis before the Basilica Martyrum was built, the only one to survive is the sacellum of San Vittore in Ciel d’Oro (now connected to the church), where Ambrose had buried his brother Satyrus (†378) next to the remains of the Mauretanian saint, Victor. The dome is a light structure composed of terracotta pipes, its interior covered with precious mosaics dating to the fifth or sixth century. The golden dome is embellished with a depiction of St Victor, who wears the jewelled crown of martyrdom. The walls are decorated with the pairs of martyrs of the Milanese Church – Nabor and Felix; Protasius and Gervasius – accompanied, respectively, by Bishop Maternus and Ambrose, the two bishops who found their bodies. The depiction of Ambrose is marked by a realism that suggests it was drawn from an official portrait made when he was young and still a governor.